In the early stages of any cleantech sector, the industry often falls into the trap of being “gadget-driven.” Engineers and scientists develop impressive technologies—innovative “hammers”—and then scour the landscape looking for problems—”nails”—that their technology might solve. While this technology-push approach has birthed the biocharBiochar is a carbon-rich material created from biomass decomposition in low-oxygen conditions. It has important applications in environmental remediation, soil improvement, agriculture, carbon sequestration, energy storage, and sustainable materials, promoting efficiency and reducing waste in various contexts while addressing climate change challenges. More industry, the sector’s maturation demands a pivot toward a market-pull strategy.

The next phase of biochar commercialization belongs to project developers who reverse this equation: identifying the unmet market needs first, and then selecting the most appropriate, scalable technology to address them. This “nails before hammers” philosophy is exemplified by recent moves from developers like Clean Earth Innovations, who are leveraging a background in software and serial entrepreneurship to treat biochar not just as a product, but as a mechanism for circular economic integration.

For investors, equipment manufacturers, and buyers, this shift signals a move away from science experiments toward infrastructure-grade project development. This analysis explores how this market-driven methodology is playing out in key regions like Florida, the implications for feedstockFeedstock refers to the raw organic material used to produce biochar. This can include a wide range of materials, such as wood chips, agricultural residues, and animal manure. More strategy, and the diversification of end-use markets beyond agriculture.

The “Nails Before Hammers” Methodology

The fundamental challenge in scaling biochar has rarely been a lack of pyrolysisPyrolysis is a thermochemical process that converts waste biomass into bio-char, bio-oil, and pyro-gas. It offers significant advantages in waste valorization, turning low-value materials into economically valuable resources. Its versatility allows for tailored products based on operational conditions, presenting itself as a cost-effective and efficient More technology; it has been the misalignment between production capabilities and market realities. A “gadget-driven” company might build a facility because they have a proprietary reactor design. A market-driven company builds a facility because a municipality is running out of landfill space, or a data center needs transparent Carbon Dioxide Removals (CDRs).

Clean Earth Innovations, led by Harold Gubnitsky, illustrates this rigorous commercial discipline. By applying a methodology honed in the software and biotech sectors, the company identifies “nails”—specific, unmet market demands such as the need for transparent CDRs or regional water remediation—before selecting the “hammer” (technology) to solve them. This technology-agnostic approach is critical for risk mitigation. By not being overly attached to a single proprietary technology, a developer retains the flexibility to deploy the right solution for the specific feedstock and offtake requirements of a given project.

For the broader industry, this suggests that the most successful project developers will likely be those who treat technology vendors as partners rather than being vendors themselves. This separation of powers allows developers to focus on what matters most to investors: financial sustainability, permitting, and offtake security.

Strategic Regional Deployment: The Florida Case Study

Florida is rapidly emerging as a microcosm of the broader biochar opportunity, driven by a convergence of feedstock availability, environmental pain points, and a pragmatic regulatory environment.

Feedstock Abundance and Diversity

The state offers a rich tapestry of biomassBiomass is a complex biological organic or non-organic solid product derived from living or recently living organism and available naturally. Various types of wastes such as animal manure, waste paper, sludge and many industrial wastes are also treated as biomass because like natural biomass these More. Beyond the standard agricultural residues, Florida faces unique waste streams, such as biomass from orange groves being removed due to disease or land conversion, and significant volumes of green yard waste.

The strategy here involves distinct project archetypes based on feedstock characteristics:

- Urban/Municipal Integration. In Miami-Dade County, the focus is on diverting green yard waste from landfills. The “nail” here is the preservation of precious landfill capacity and the reduction of methane emissions from decomposing organic matter.

- Industrial Co-Location. The company is exploring opportunities for co-location with woodmills. Utilizing wood chips provides a consistent, high-carbon feedstock ideal for producing standardized biochar.

This bifurcation—opportunistic urban waste diversion vs. consistent industrial co-location—demonstrates how developers must adapt their business models to local resources. The Miami-Dade project, a demonstration facility sitting atop a landfill, serves as a proof of concept for the circular economy, transforming a waste liability into an asset while creating green jobs.

The Water Remediation Opportunity

While soil amendmentA soil amendment is any material added to the soil to enhance its physical or chemical properties, improving its suitability for plant growth. Biochar is considered a soil amendment as it can improve soil structure, water retention, nutrient availability, and microbial activity. More remains the volume leader for biochar discussions, water remediation represents a higher-value “nail,” particularly in regions like Florida with sensitive aquatic ecosystems. The state’s focus on water quality creates a natural demand for biochar’s filtration properties. Developers are increasingly viewing water remediation not just as a niche application, but as a primary driver for project economics, potentially layering intellectual property on top of standard biochar production to enhance filtration efficacy.

Technology Agnosticism and Scalability

For equipment manufacturers, the rise of the independent project developer is a positive indicator of market health. It means that technology selection is becoming meritocratic.

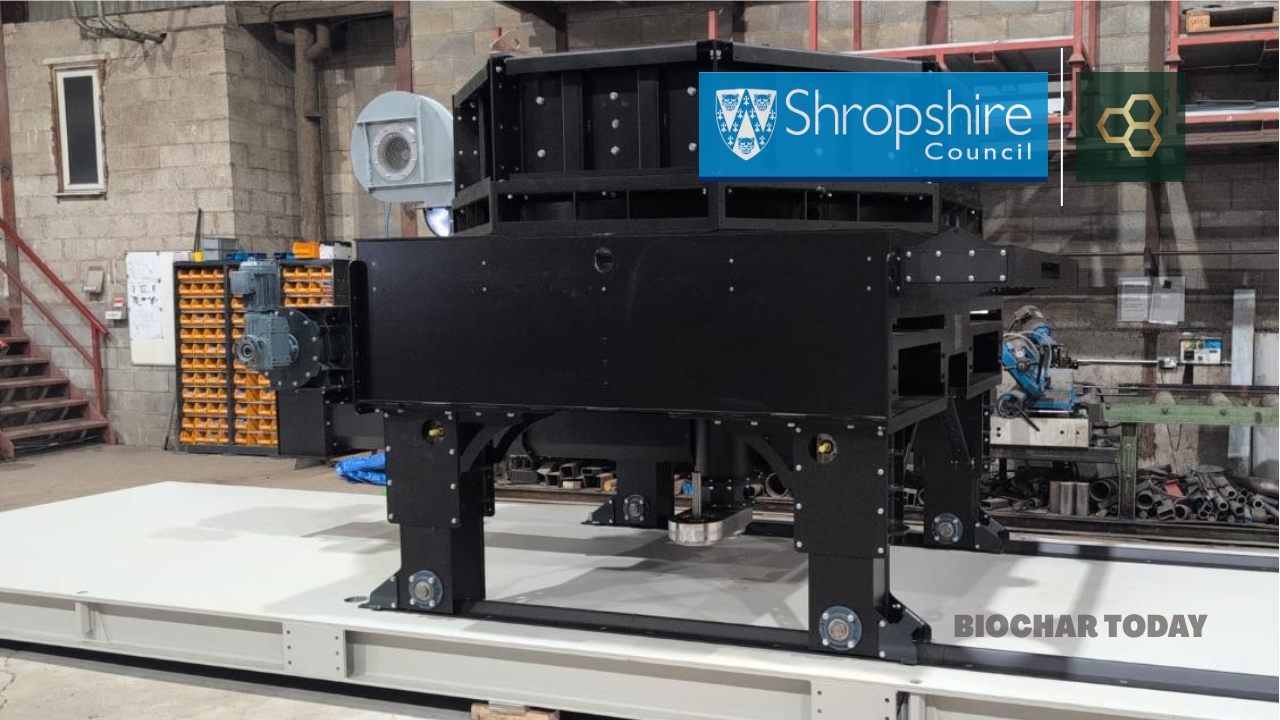

Clean Earth Innovations, for instance, has selected BET technology for its Miami-Dade deployment but remains open to other vendors for future projects. This suggests that manufacturers who can demonstrate reliability and scalability—moving from “science project” to “industrial plant”—will win market share.

The scale of these ambitions is significant. The project pipeline discussed involves potential throughputs of hundreds of thousands of tons annually across multiple sites. For such volumes, the reliability of the “hammer” is paramount. And manufacturers must be prepared to support 24/7 operations where downtime directly impacts municipal waste contracts and CDR delivery schedules.

Diversifying End Markets: Beyond the Soil

A persistent bottleneck in the biochar industry is the education gap in the agricultural sector. While the agronomic benefits are clear, changing farming practices is a slow process. Consequently, sophisticated developers are diversifying their offtake strategies to include more immediate or higher-value markets.

Green Construction Materials

The “built environment”—concrete, asphalt, and steel—is emerging as a massive potential sink for biochar. While currently in the research and pilot phase, the excitement around “green steel” and carbon-negative concrete is palpable. These applications offer a pathway to sequester vast amounts of carbon in long-lived infrastructure, aligning perfectly with the permanence requirements of the high-quality CDR market.

The CDR Market

The demand for Carbon Dioxide Removals remains a critical financial pillar. Large corporate buyers (tech companies, oil majors) are actively seeking transparent, permanent offsets to mitigate their footprints. However, the market is becoming more discerning. “Forward commitments” and Letters of Intent (LOIs) are increasingly tied to strict quality and deployment standards. A developer cannot simply produce char; they must prove its sequestration.

The “flexible production line” concept is an innovative response to this dynamic. Future facilities may operate multiple lines: some optimized for high-quality biochar for CDR generation and agriculture, and others producing industrial biocarbon for applications like green steel where CDR methodologies might be different or less prioritized. This flexibility allows the developer to pivot based on fluctuating carbon prices and commodity demand.

Navigating the Regulatory and Social Landscape

No biochar project exists in a vacuum. Successful deployment requires navigating complex regulatory environments and community relations.

The “Incineration” Misconception

A major hurdle for the industry is distinguishing pyrolysis from incineration. The language used matters immensely. Describing the process as “baking and transforming” rather than “burning” is essential to avoid conflation with mass-burn incinerators, which often face stiff community opposition.

Permitting Realities

The regulatory experience in Florida offers a template for other regions. A “practical” approach from air permitting teams, who are educated on the distinct emissions profile of pyrolysis versus landfilling, can significantly accelerate project timelines. When regulators understand that biochar production actually prevents emissions (by diverting waste that would otherwise rot and release methane), permitting becomes a collaborative rather than adversarial process.

Community Engagement

The Miami-Dade project highlights the value of aligning with local political mandates. When a project supports a county’s zero-waste goals and receives backing from leadership (such as Mayor Cava Levine’s green mandates), it gains a “license to operate” that goes beyond mere legal permits. Engaging the community—holding events at the site, demonstrating the circularity of the process—turns a “waste facility” into a point of civic pride.

The Financial Trinity: Innovation, Environment, Economics

Clean Earth Innovations’ three-pillar framework for long-term viability — Innovation, Environment, and Financial Success — is a model for the biochar industry as a whole.

- Innovation. Identifying the right market needs and adapting technology to meet them.

- Environment. Delivering genuine, measurable impact (CDR, landfill diversion, water quality).

- Financial Success. Ensuring projects are economically sustainable without indefinite reliance on grants or subsidies.

As the industry moves forward, the most exciting developments will not necessarily be a new type of reactor, but rather the business model innovations that allow these reactors to be deployed at scale. The transition from “finding nails for our hammers” to “finding hammers for the nails” marks the maturing of biochar from a niche technology to a cornerstone of the global circular economy.

For investors and industry watchers, the key metric to watch is no longer just “production capacity” but “integrated project viability.” Companies that master the complex interplay of feedstock security, technology reliability, and diversified offtake will define the next decade of the biochar sector. As Gubinsky remarks, we must aim to make “original mistakes” —learning from the past to push the boundaries of what is possible in this critical industry.

Leave a Reply