Key Takeaways

- Short DNA strands are absorbed by biocharBiochar is a carbon-rich material created from biomass decomposition in low-oxygen conditions. It has important applications in environmental remediation, soil improvement, agriculture, carbon sequestration, energy storage, and sustainable materials, promoting efficiency and reducing waste in various contexts while addressing climate change challenges. More at much higher rates than long strands because they can fit into the material’s tiny internal pores.

- Biochar produced at higher temperatures has a much greater capacity to trap DNA due to its larger surface area and higher level of carbon stability.

- Once DNA is attached to biochar, it undergoes a change in shape but does not break apart, allowing it to remain stable and protected.

- Long DNA strands are more difficult to remove from biochar once they are attached because they anchor themselves at multiple points.

- Natural forces like water-repelling interactions and specific chemical attractions are the primary reasons DNA sticks so effectively to biochar surfaces.

The environmental fate of genetic material is a growing concern for scientists, particularly regarding how antibiotic resistance genes persist in soil and water. In a study published in the journal Water Research X, researchers Xiao Sun, Lin Shi, Huang Zhang, Fangfang Li, Yanjin Long, Di Zhang, and their team explored how biocha interacts with different lengths of DNA. Their work reveals that the way DNA attaches to biochar is not a one-size-fits-all process but depends heavily on the size of the DNA and the specific properties of the biochar used.

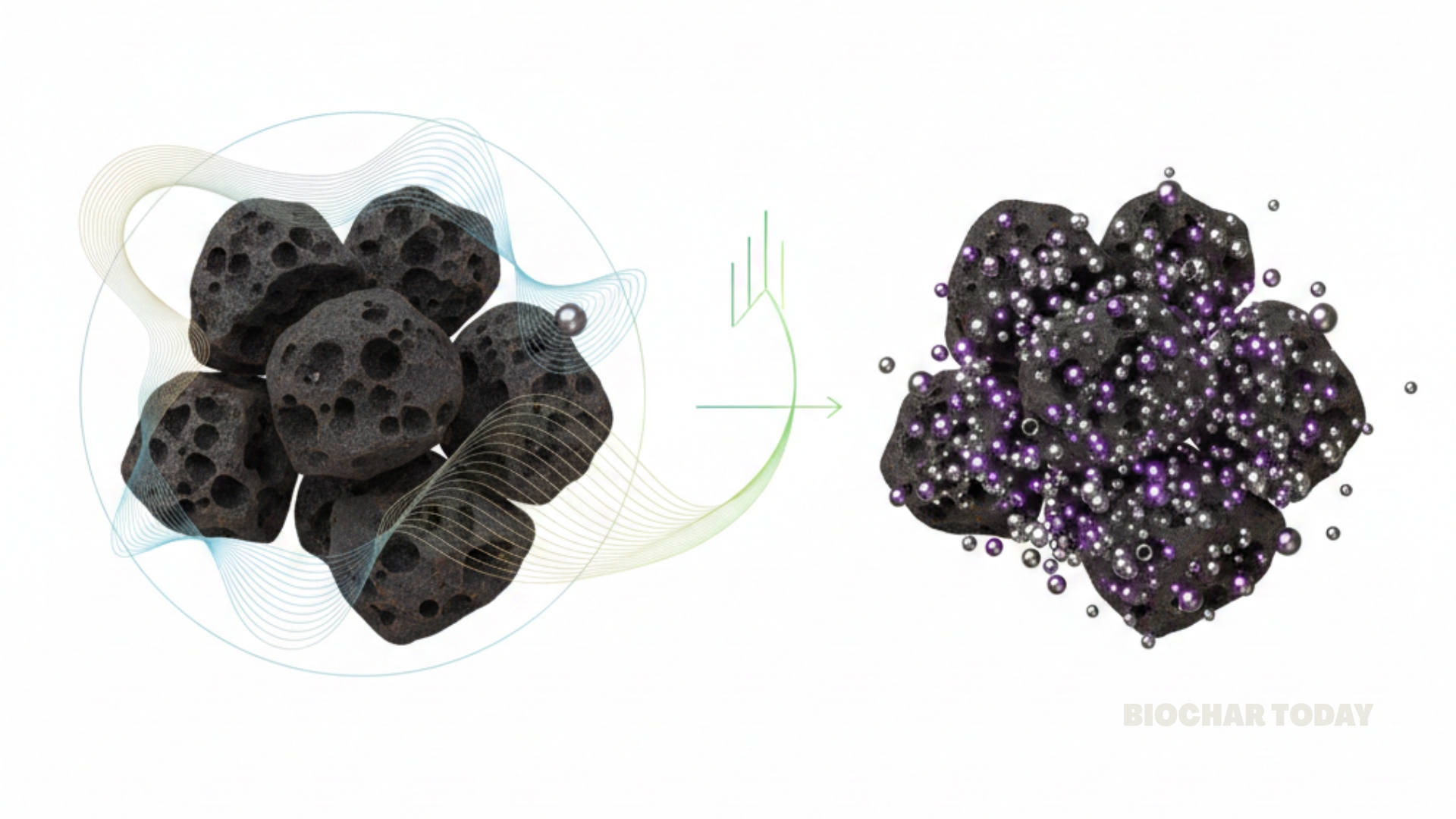

The team discovered that short-stranded DNA has a significantly higher adsorption capacity compared to long-stranded DNA. Specifically, on biochar produced at high temperatures, short DNA reached an adsorption capacity of 5.91 milligrams per gram, while long DNA only reached 2.22 milligrams per gram. This difference occurs because short DNA fragments are small enough to travel into the internal mesopores of the biochar. In contrast, long DNA strands are physically too large to enter these small spaces, meaning they can only attach to the outer surface of the biochar particles.

While short DNA is absorbed in greater quantities, long DNA is much harder to wash away once it has attached. The study found that long DNA strands use a multisite anchoring mechanism, essentially sticking to the biochar at many different points along the chain. This creates a stronger bond that resists being released back into the environment. When testing the release rates on lower-temperature biochar, the researchers found that only 4% to 13% of long DNA was released, compared to 5% to 20% of the shorter strands.

The temperature at which the biochar was made also played a vital role in these interactions. Biochars produced at higher temperatures, such as 600 degrees Celsius, were much more effective at trapping DNA. These high-temperature materials have more aromatic carbon structures and less negative surface charge, which reduces the natural repulsion between the biochar and the DNA. This allows for stronger chemical attractions, such as hydrophobic forces and specialized carbon-to-carbon bonds, to take hold and secure the genetic material.

Beyond just trapping the DNA, the researchers wanted to know if the genetic material remained intact. Using advanced computer simulations and microscopic imaging, they confirmed that the DNA changed its physical shape when it contacted the biochar, but it did not fragment or break. This means the DNA remains structurally stable while bound to the carbon. This stability is a key finding for environmental safety, as it suggests that biochar could potentially act as a permanent sink for certain types of genetic material, preventing it from moving freely through the ecosystem.

Ultimately, this research provides a clearer picture of how we can use engineered materials like biochar to manage biological components in our environment. By understanding that shorter DNA fragments are more likely to be absorbed while longer ones are more likely to stay stuck, scientists can better predict how genetic information, including resistance genes, will behave in different soil conditions. This study marks an important step in managing the ecological impacts of biochar and controlling the spread of genetic materials in the wild.

Source: Sun, X., Shi, L., Zhang, H., Li, F., Long, Y., & Zhang, D. (2026). Chain-length-dependent adsorption of extracellular DNA on biochar: Behaviors, mechanisms, and structural stability. Water Research X, 30, 100496.

Leave a Reply