Key Takeaways

- Most of the biocharBiochar is a carbon-rich material created from biomass decomposition in low-oxygen conditions. It has important applications in environmental remediation, soil improvement, agriculture, carbon sequestration, energy storage, and sustainable materials, promoting efficiency and reducing waste in various contexts while addressing climate change challenges. More fed to cattle survives the digestive process and can be safely returned to the soil through manure.

- The biochar that passes through the animal maintains its high quality and remains effective at trapping carbon for long periods.

- Digestion acts similarly to natural aging in soil, leaving behind the most durable parts of the biochar material.

- Using cattle as a vehicle for biochar application offers a practical way to improve soil health while fighting climate change.

- This strategy allows farmers to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by turning animal waste into a long-term carbon storage tool.

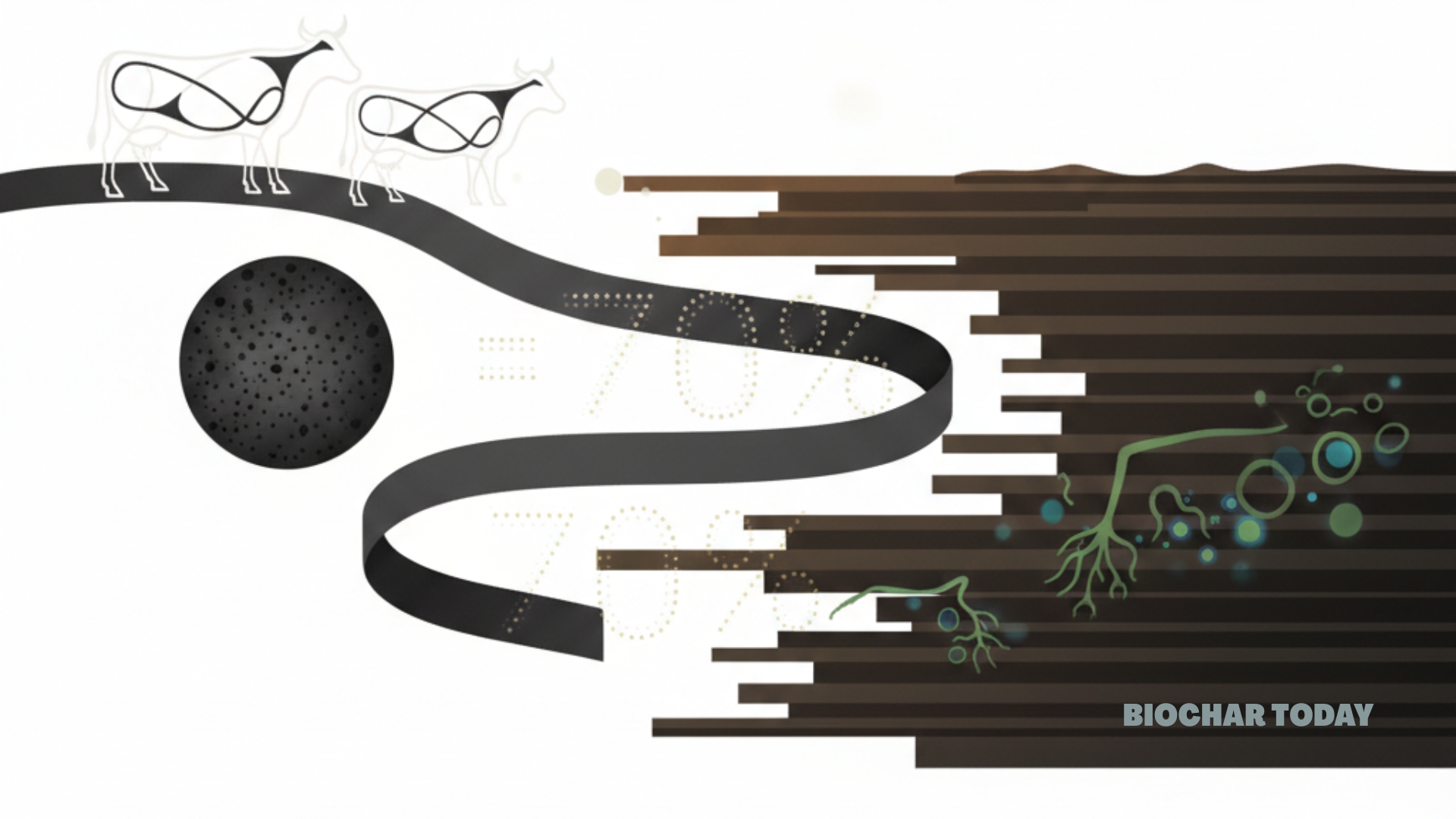

Agricultural researchers are increasingly looking for innovative ways to lower greenhouse gas emissions while maintaining the health of the land. One strategy gaining attention is the practice of adding biochar to animal feed. This approach creates a cascade of benefits, starting with the digestive health of the livestock and ending with the sequestration of carbon in the soil. Published in the journal Biochar, a study led by Iva Lucill Walz, Marie Dittmann, and Jens Leifeld investigated what happens to this material once it passes through a dairy cow. They sought to determine how much of the biochar survives the harsh environment of the gut and whether the material that remains is still useful for protecting the climate.

The findings show that biochar is remarkably resilient. After being consumed by dairy cows, the majority of the biochar—ranging from 70 to 90 percent—was recovered in the dung. This high recovery rate is significant because it proves that biochar does not simply disappear during digestion. Instead, the most stable components of the material endure. The researchers noted that the digestive process acts as a form of selective preservation. The gut environment breaks down the less stable, oxygen-rich parts of the biochar, but the most durable, condensed aromatic structures remain untouched. This effect is very similar to the short-term aging that biochar undergoes when it is placed directly into the soil.

The quality of the biochar after it leaves the cow is just as impressive as the quantity recovered. The study found that the digested material meets the strict international criteria for highly stable biochar. Specifically, it maintains the low hydrogen-to-carbon and oxygen-to-carbon ratios required for long-term carbon storage. Because the digestive system effectively “pre-ages” the biochar by removing its most vulnerable fractions, the material that eventually reaches the field is exceptionally hardy. This suggests that applying biochar through manure is not just a convenient delivery method; it may actually ensure that only the most permanent carbon is being added to the terrestrial sink.

Beyond its role in trapping carbon, biochar in dung offers other environmental advantages. Indigestible particles in the manure can help stabilize nitrogen, which potentially reduces the release of harmful gases like ammonia and methane during storage and application. This dual-action benefit makes the feed-integrated approach a promising tool for farmers looking to minimize their environmental footprint. The porous structure of the biochar also remains intact, meaning it can still fulfill its traditional role of improving soil aeration and water retention once it is spread on crops.

The study utilized three different testing methodologies to confirm these results, including thermal analysis and elemental analysis. While each method provided different insights, they all converged on the same conclusion: biochar is a tough material that can withstand the biological and chemical rigors of a cow’s digestive tract. This provides a scientific foundation for using livestock as a primary vehicle for carbon sequestration. By feeding biochar to cattle, farmers can utilize existing manure management systems to distribute stable carbon across their fields. This creates a circular agricultural system where feed additives contribute directly to the fight against atmospheric warming.

In summary, the research highlights a viable pathway for mitigating agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. The high survival rate of the stable carbon structures within the biochar ensures that the material will function as a long-term carbon sink for centuries. This strategy turns a standard farming practice into a powerful environmental service, offering a scalable solution for improving soil fertility and sequestering carbon simultaneously. As agricultural sectors worldwide face pressure to reach net-zero goals, integrating resilient materials like biochar into the livestock cycle could become a cornerstone of sustainable land management.

Source: Walz, I. L., Dittmann, M., & Leifeld, J. (2026). Recovery and composition of biochar after feeding to cattle. Biochar, 8(13).

Leave a Reply