Key Takeaways

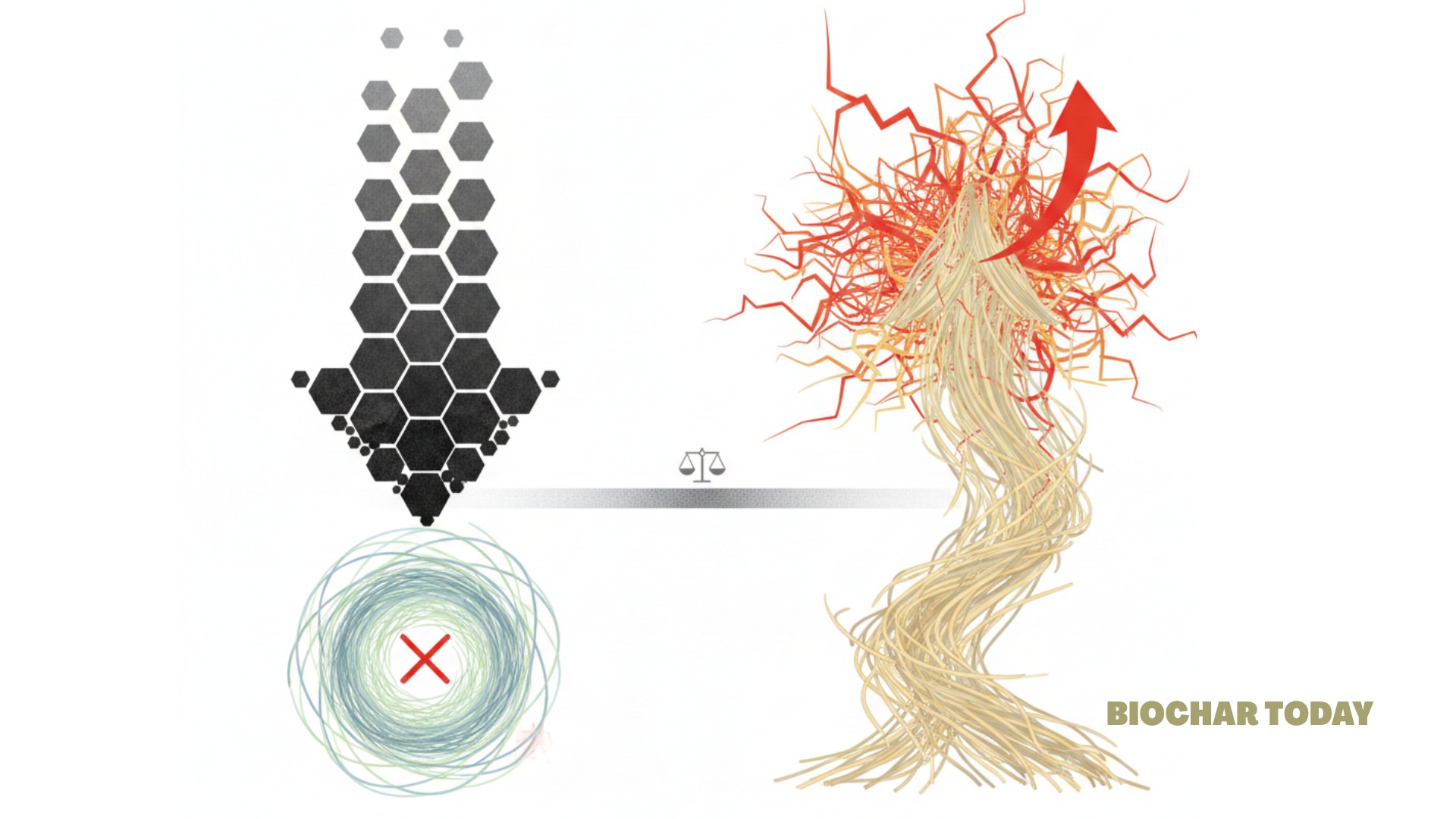

- Raw maize straw applied to soil increases harmful nitrous oxide emissions by up to 27%.

- Converting that same straw into biocharBiochar is a carbon-rich material created from biomass decomposition in low-oxygen conditions. It has important applications in environmental remediation, soil improvement, agriculture, carbon sequestration, energy storage, and sustainable materials, promoting efficiency and reducing waste in various contexts while addressing climate change challenges. More reverses the effect, cutting emissions by nearly 20%.

- Biochar works by suppressing the bacteria that create nitrogen gas and boosting those that consume it.

- Applying alkaline biochar to acidic forest soils improves overall soil health and nitrogen management.

The research, published in the journal Biochar by Mouliang Xiao and a team of international scientists, reveals a striking contrast in how organic soil amendments affect the atmosphere. When farmers or forest managers add raw maize straw to the soil, it acts as a quick-release fuel for microbial activity. This surge in nutrients stimulates specific bacteria that produce nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas significantly more potent than carbon dioxide. In the subtropical Moso bamboo forests of China, this common practice was found to increase gas emissions by 16% to 27%.

The story changes completely when that straw undergoes pyrolysisPyrolysis is a thermochemical process that converts waste biomass into bio-char, bio-oil, and pyro-gas. It offers significant advantages in waste valorization, turning low-value materials into economically valuable resources. Its versatility allows for tailored products based on operational conditions, presenting itself as a cost-effective and efficient More to become biochar. Biochar manages nitrogen in a much more disciplined way. Instead of flooding the soil with nutrients, biochar decreases the concentrations of available ammonium and nitrate by roughly 11% to 15%. This scarcity of raw materials for gas-producing microbes is the first line of defense against emissions. By essentially locking away some of the nitrogen, biochar prevents the rapid chemical spikes that lead to gas leaks from the soil.

Beyond just managing chemicals, biochar reshapes the entire microbial neighborhood. The study found that biochar significantly reduced the abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria by up to 45%. These are the specific organisms responsible for the first steps of the nitrogen cycle that eventually lead to gas production. Furthermore, biochar inhibited several key genera of bacteria, such as Nitrosospira and Pseudomonas, which are known drivers of the denitrification process. By cooling down the activity of these microbial “hotspots,” biochar keeps the nitrogen in the ground rather than letting it escape into the air.

Perhaps the most impressive trick biochar performs is its ability to boost the “consumers” of nitrous oxide. The researchers discovered that biochar application increased the abundance of the nosZ gene by up to 46%. This gene allows certain beneficial bacteria, like Mesorhizobium and Azospirillum, to transform nitrous oxide into harmless nitrogen gas before it ever leaves the soil surface. In contrast, raw straw was found to inhibit these helpful microbes, further contributing to the buildup of greenhouse gases.

This research suggests that how we return agricultural waste to the earth matters just as much as the act of returning it. While straw return is a well-meaning strategy for recycling nutrients, in its raw form, it may inadvertently accelerate climate change in specific forest environments. Converting that waste into biochar offers a dual benefit: it restores the soil and protects the atmosphere. For the vast Moso bamboo forests that cover millions of hectares, switching to biochar-based management could become a vital tool for environmental conservation and climate mitigation.

Source: Xiao, M., Tang, C., Jiang, Z., Zhou, J., Luo, Y., Ge, T., Pan, L., Yu, B., Cai, Y., White, J. C., & Li, Y. (2026). Opposing effects of maize straw and its biochar on soil N2O emissions by mediating microbial nitrification and denitrification in a subtropical Moso bamboo forest. Biochar, 8, 50.

Leave a Reply